Berghahn & Sternberg, “Locating Migrant and Diasporic Cinema in Contemporary Europe”

Huat, “East Asian Pop Culture”

Thussu, “Cultural Practices and Media Production: the Case of Bollywood”

Pop culture in general has, in the past, often been held in a lower esteem and dismissed as commercial and lacking depth in contrast to “high culture”. However, the rapid expansion of the creative industries and in particular the globalization of the media landscape has brought attention from governments and scholars as possible redefined spaces for the practice and analysis of “soft power”. Entertainment has always been inherently political in nature, yet, the transnationalization of media means that there is an expansion of the cultural public sphere where ideologies and values can be discussed and debated. However, this internationalization of the media apparatus means that there has been internationalization in the software of culture and media as well. Such examples of internationalization and possible homogenization can easily be seen when studying media flows from South to West, for instance the global rise of Bollywood cinema or the development of Asian pop culture.

Governments have seen the potential of media as a instruments of “soft power”, which can be defined as “the use of different cultural resources […] to project a positive image of a nation in order to influence the perceptions and views of others of the nation and to generate goodwill in international relations and trade for the nation” (Huat, 2011: 241). Consequently, the interest of governments in the production of media is not simply economic but also highly ideological, it is a way of appropriating a culture, of branding a nation, of situating it within a larger global framework… therefore the consumption of mass entertainment “has acquired a new layer of political significance and consequence” (Huat 2011: 243). However, the danger of such developments is the creation of a new form of hegemony as is the case with Bollywood: it is now seen not only as a creative enterprise but a “global brand” that is “increasingly shaped by a Hollywoodized sensibility and aesthetics” (Thussu, 2012: 132) embodied by movies such as Slumdog Millionaire. In cases like these, only a particular side of a culture is being promoted. Could this in turn be forcing upon us a way of seeing the world? And could it be potentially distracting us from other issues that require more attention? We would like to analyze further the politics of transnational media, soft power and the role of media in the cultural public sphere through a case study of the 2009 film District 9.

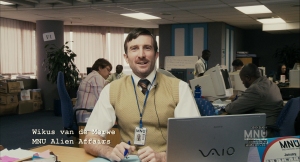

District 9 is a science fiction film that takes place in present day Johannesburg, South Africa where 20 years earlier an alien ship crashed with it onboard 1 million starving, weak insect-like aliens. The aliens are housed in a refugee-like camp in the city called District 9 but because of their encroachment on local communities a plan is set in place to relocate them to the outskirts of the city. The film is reminiscent of actual events that happened in apartheid South Africa when an area of Cape Town was designated as “whites only” and the 60 000 non-white inhabitants of District 6 were forcibly relocated to a township complex outside the city limits. The film, although considered independent, was born out of collaboration between Hollywood producer Peter Jackson and South African director Niell Blomkamp. It is no doubt a product of the transnationalization of media, yet can it be considered to be World Cinema? It resonates with Western aesthetics; in fact, it is primarily Western aesthetics with the South African local flavor. The film could have taken place in any backdrop without compromising its integrity. However, the political sub-narrative would have been a lot less obvious. The film is shot in a documentary style, which gives is it an eerie feeling of reality and authenticity, and so the viewer feels like this is indeed happening in real life although being science fiction. Using the PESTEL model of analysis the plot deals with segregation with a parallel made with apartheid and present day refugees (political), poverty and conditions of life in slums and temporary camps (economic) as the scenes are shot in an actual emptied shantytown, xenophobia and racism through the use of speciesism (social), the fear of modern technology embodied in the mutation that takes place while misusing alien technology (technology), the pollution caused by inadequate housing (environmental), and the government’s role in forced relocations and removals and the rights of minorities (legislative). However, it may also be relevant to expand it to the STEEPLED model incorporating ethics and demographics into our analysis. The problems the movie addresses are universal such as immigration, poverty, social cohesion, and crime. These problems are everyday occurrences in South Africa yet they also occur all over the world, which adds to the movies global appeal.

The film definitely confirms the use of soft power as it contains a highly political message and was a successful box office hit. However, the movie also fits into the migrant and diasporic cinema narrative despite taking a more supra-level approach: In District 9 the aliens are the migrant population, only out of necessity settling in Johannesburg. Their displacement is not only physical, as they are from a different world, but also on a politico-juridical base as they are being discriminated. The narrative is also in line with Homi Bhabha’s concept of a “Third Space” as a contact zone, a social space where disparate cultures meet, clash and grapple with each other often in highly asymmetrical relations of domination and subordination’. The world in District 9 is like this Third Space. But it could also be argued that the film itself creates a third space or at least a contact zone where it is possible to negotiate these issues. It is in a way a collaborative work between the colonizer and the colonized (or the West and the South): it challenges the national through the use of western aesthetics and its global appeal yet remains of local concern. Can we speak here of “Glocalization”?

Nonetheless, there is an interesting tension in the movie: on the one hand, the blacks (who used to be discriminated) become the center, the discriminators. On the other hand, by making this movie, it functions as a redemption of the marginalized, the ‘truth is revealed’. Yet, it could also be argued that the film employs the widely used Hollywood “white savior narrative”, similar to that of Avatar, where a story of segregation is turned into the story of a man from the majority perspective. The enthrallment of science fiction is its ability to break away from the familiar and be radically new, and despite being a good example of soft power and the creation of a space where ethics, ideologies and values can be discussed, District 9 fails at breaking away from the hegemony of Hollywood in global media production.